The scheduled Olympics in 1916 were canceled due to World War I. While the Olympics resumed in 1920, a seminal event featuring renowned athletes from across the world took place in 1919 in the aftermath of the first truly global conflict in human history.

The sudden end to the fighting in France on Nov. 11, 1918 took American military officials by surprise. Leadership had given very little thought to the difficulties of demobilizing a mass army in an efficient and equitable manner, particularly for soldiers stationed overseas. Authorities, concerned that peace negotiations might break down and the military would be forced to fight again, imposed a steady diet of daily drills, target practice and tactical exercises. Low morale over the continued training and the slow pace of demobilization reached near crisis proportions just as a third wave of influenza hit the debarkation camps in France. This created tremendous bitterness among troops who watched their comrades fall ill and die while awaiting transport home. Clearly, something voluntary and enjoyable was needed to unite the troops and occupy their time until the War Department could get them all home.

Sports competitions offered the ideal solution. And, thus, the Inter-Allied Games was born.

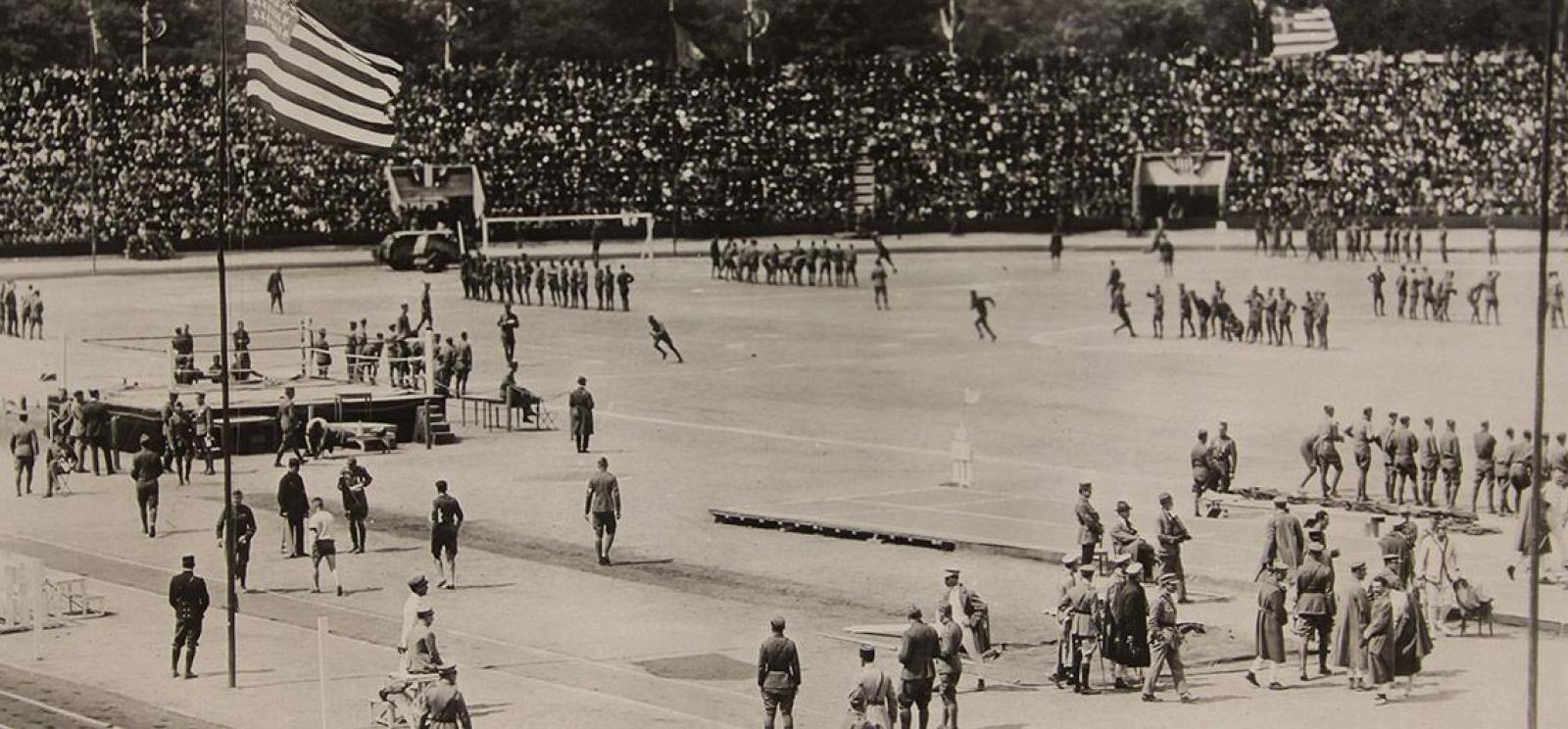

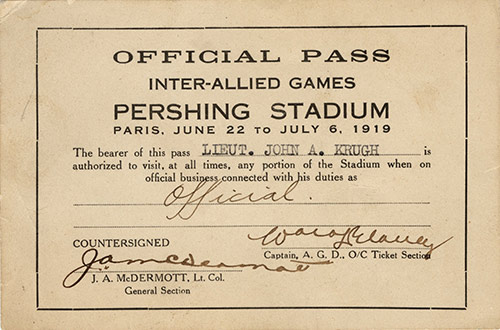

Held from June 22 – July 6, 1919 outside of Paris near the site of the 1900 Olympics, the Inter-Allied Games featured hundreds of male athletes from nations across the world aligned with the Allies during World War I competing in 13 sports. During the course of the completion, more than 500,000 spectators witnessed some of the globe’s best athletes – past, present and future.

“The passage of time has led to lapse in familiarity with the Inter-Allied Games,” said National WWI Museum and Memorial Senior Curator Doran Cart. “This was a world-class competition featuring some of the best athletes in the world. Perhaps more importantly, the Inter-Allied Games served as a vehicle for healing the wounds from the most catastrophic war to that time in human history.”

On Feb. 24, 1919, the YMCA signed a contract for the construction of a 20,000 seat stadium for use during the Inter-Allied Games with an aggressive schedule of completion targeted for May 26. The YMCA provided the necessary funds ($100,000) for the construction of the stadium which, when completed, was to be turned over to U.S. General John J. Pershing (it was named for him as well). Pershing, in turn, would present it to the proper French authorities as a memorial to the American Expeditionary Forces. By the end of April, the labor situation was uncertain when a general strike was threatened for May 1, which would have made it impossible for the contractors to fulfill their obligations. Military troops were called in to assist. American engineers and labor troops, in their olive drab uniforms, worked night and day on the stadium along with a force of about 300 French soldiers. When completed, the peripheral measurement of Pershing Stadium was 2,100 feet, enclosed nine acres of field and was 100 yards long.

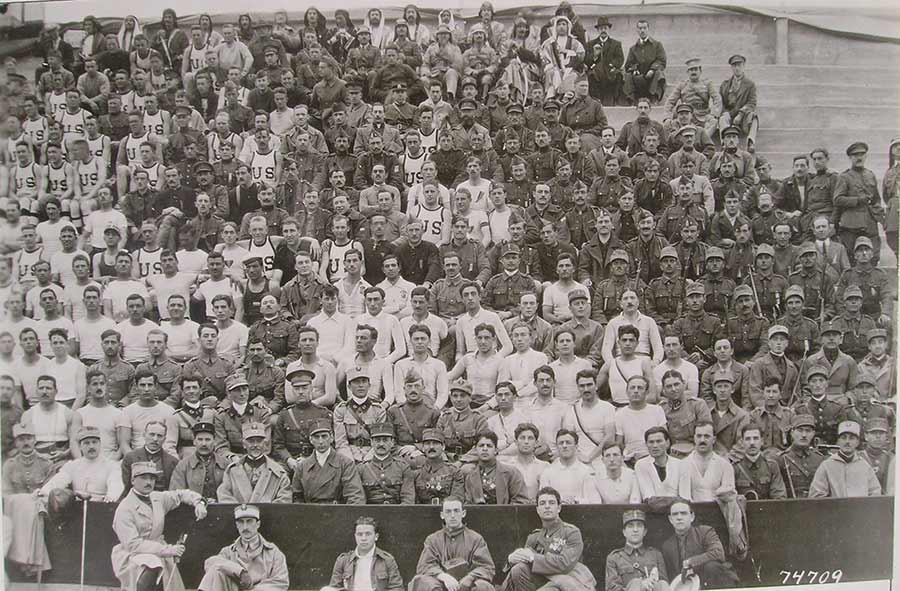

An Olympics-style opening ceremony featuring more than 1,500 participants was held and athletes from 14 nations competed, including Australia, Belgium, Canada, Czecho-Slovakia (as it was known in 1919), France, Hedjaz (Arabia), Italy, the U.K., the U.S. and more. Women were not allowed to compete.

Competitions were held in a number of sports, including baseball, basketball, boxing, football, golf, swimming, track and field, tennis and even hand grenade tossing. Participants included several famous tennis players, including previous/future Wimbledon champions Andre Gobert (France), Randolph Lycett (Australia) and Pat O’Hara Wood (Australia).

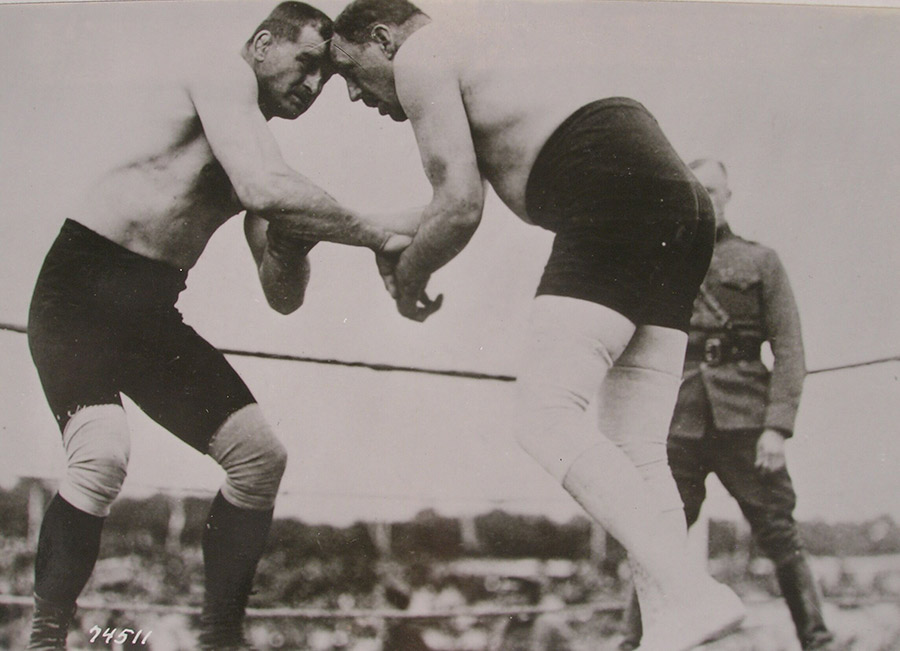

The boxing competition featured future world heavyweight champion Gene Tunney. Future wresting world middleweight champion Ralph Parcaut (U.S.) competed and future president of the National Boxing Association (later the World Boxing Association) Paul Prehn captured the middleweight gold medal in wrestling. U.S. Army chaplain F.C. Thompson set a world record in the newly created sport of hand grenade tossing with a mark of 245 feet, 11 inches.

An article in the New York Times, dated July 6, 1919, stated that the crowd at the Inter-Allied Games “loudly cheered the negro private Solomon ‘Sol’ Butler, the American broad jump champion.” His prowess shone as a soldier in the American Expeditionary Forces, despite the prejudices he faced as an African American. He won the running long (broad) jump competition with a leap of nearly eight meters – just shy of the Olympic record. Butler was the only African American to medal during the event. He later went on to play in the National Football League (alongside Jim Thorpe with the Canton Bulldogs) as well as the Negro Baseball League. Eventually, he was an inaugural inductee into the National High School Track and Field Hall of Fame (along with other notables such as Jesse Owens and Steve Prefontaine).

Arguably the greatest individual achievement came from American swimmer Norman Ross, who won the 100m, 1,500m and 400m freestyle events, the latter in a world-record time of 5 minutes, 40 seconds. Ross eventually won three Olympic gold medals and set 13 world records during his career.

After more than two weeks of competition, the event concluded with an extravagant closing ceremony on July 6. Bands in the crowded stadium played the “Star-Spangled Banner” followed by the “Marseillaise,” and the flags of the Allies were slowly lowered with more than 30,000 spectators witnessing the stadium being gifted to France. On that last afternoon, prizes were awarded to the winners by General Pershing and the French flag, alone, was hoisted over the Stadium for the first time.

The Inter-Allied Games, one of the most unique athletic events ever contested, served as a fitting testament to the conclusion of World War I – the first conflict in human history in which every inhabited continent participated, resulting in destruction and carnage unlike anything the world had ever seen.