When the 19th Amendment took effect on Aug. 18, 1920, it followed over a century and a half of activism by and for women. Passed by Congress on June 4, 1919, the constitutional amendment promises, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by a State on account of sex.” Although 1920 is often celebrated as the year that women won the right to vote, in some parts of the U.S., women already had that right — and in other places, women would be denied the right for many years to come.

Abigail Adams foresaw how difficult it might be to persuade men in power to extend rights to other groups when she implored her husband to “remember the ladies” in March 1776. Women lacked more than the right to vote. For much of the 19th century, the legal custom of “coverture” linked a woman’s legal identity with her father or husband. Married women were thus prohibited from owning or inheriting property, controlling finances and entering contracts or lawsuits. Enslaved women were considered property themselves, and their children were born enslaved. Free Black women had even fewer opportunities and protections than white women. When afforded the right to vote, women and African Americans exercised it; in New Jersey, the state constitution granted suffrage to property-owning residents regardless of race and gender until 1807.

The first and most successful political efforts of women revolved around their role as the moral center of American society, advocating for causes like temperance, child labor laws and the abolition of slavery. In the 1830s, states began the long process of dismantling coverture by passing married women’s property acts. Originally designed to protect family assets, these laws gave women the right to own and eventually control property. By the 1840s, an organized women’s rights movement had formed, led by women like Sarah and Angelina Grimké, Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony and Sojourner Truth. They spoke out at a time when few Americans had witnessed a woman speak publicly — it was Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s and Lucretia Mott’s exclusion from the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840 that led them to organize the first Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls in 1848. The convention resolved to secure women’s “sacred right to the elective franchise,” publicly addressing women’s suffrage as a political resolution for the first time.

The Civil War put the question of suffrage on hold. The issue did not come to a head until the proposal of the 14th and 15th Amendments, which divided the women’s rights movement. In 1866, women’s suffragists objected to the wording of the proposed 14th Amendment, which defined “citizens” and “voters” as male. The 15th Amendment then introduced language to grant suffrage regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” but not gender. The Republican Party adopted the cause of Black suffrage, while Anthony and Stanton continued to campaign for women’s suffrage, adopting anti-Black racist rhetoric and enlisting the help of outspoken racist George Francis Train in the process.

Anthony and Stanton’s opposition to the 15th Amendment split the women’s suffrage movement between two groups: their women-only National Woman Suffrage Association, which condemned the 15th Amendment and advocated broadly for women’s rights, and the American Woman Suffrage Association, which focused on achieving women’s suffrage by constitutional amendment at the federal or state level under the leadership of Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell and Julia Ward Howe. The groups worked separately for two decades, a time that saw the introduction of a failed woman’s suffrage amendment in 1878 by California Senator Aaron A. Sargent, a friend of Anthony’s. In 1890, the two groups merged again to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

From the earliest days of the women’s suffrage movement, Black activists like Truth and Frances Watkins Harper spoke out against the racism they observed in the movement’s organizations and leadership, which did not share the priorities of their Black members or provide opportunities for them to lead. As the 20th century approached, both Northern and Southern states had instituted segregation and Jim Crow laws to varying degrees, and lynchings targeted African Americans in rising numbers. Black women were vulnerable to the effects of both racism and misogyny, particularly in the South, with lower wages, less educational opportunity and less power to advocate politically for themselves than was afforded to Black men and white women. Many Black women found their concerns better represented by African American activists including W.E.B. Du Bois, Ida Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell and organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Black women’s clubs that made up the National Association of Colored Women.

National attention turned again to the women’s suffrage movement in the early 1900s as a tide of reform instituted social, political and economic change. In 1913, the Women’s Suffrage Parade marched on Washington, D.C., a procession that took several hours due to the harassment of its participants. Organized by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns for the NAWSA, it was the first organized march on Washington for a political cause: amending the constitution to give women the vote. This march was itself segregated, placing Black women’s groups from Howard University at the end of the procession.

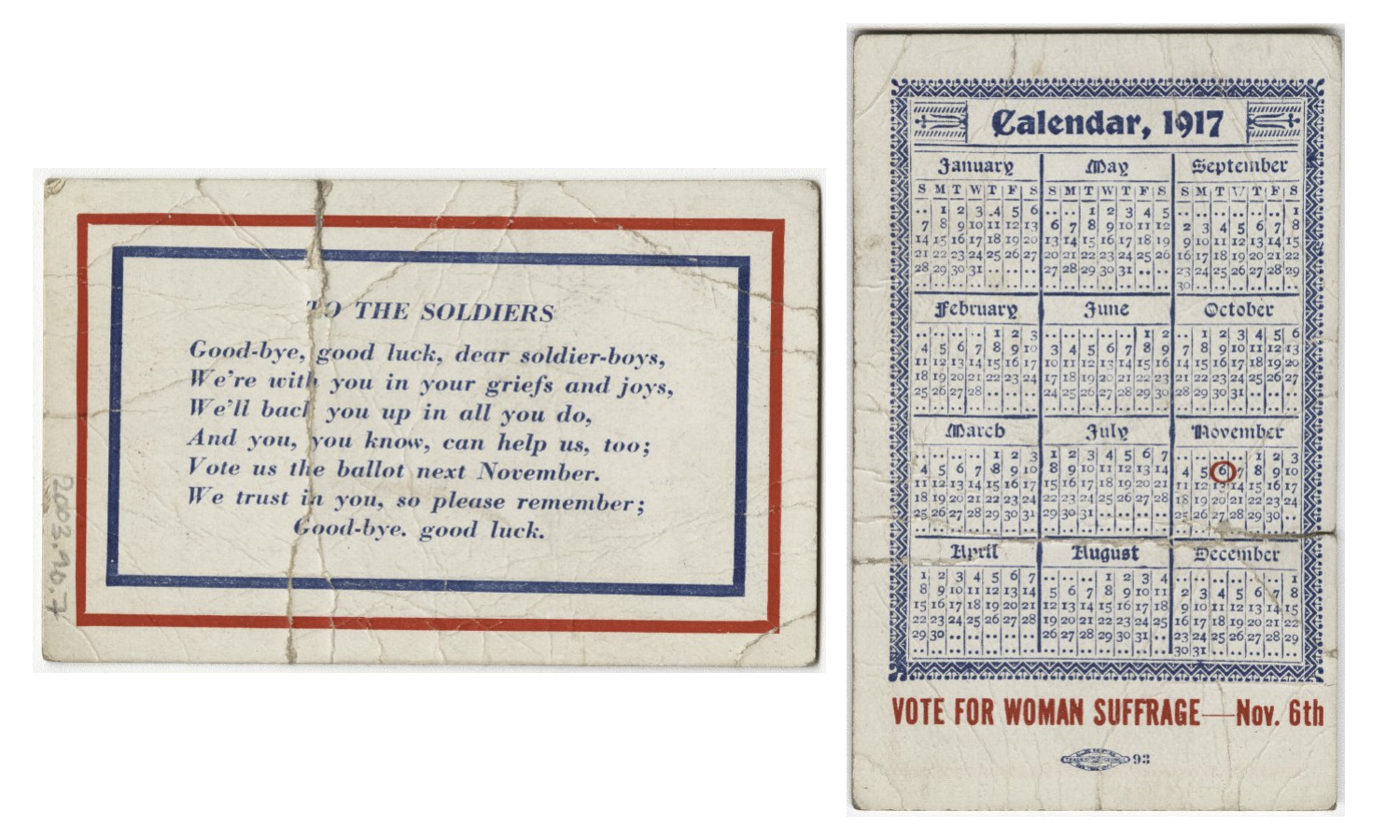

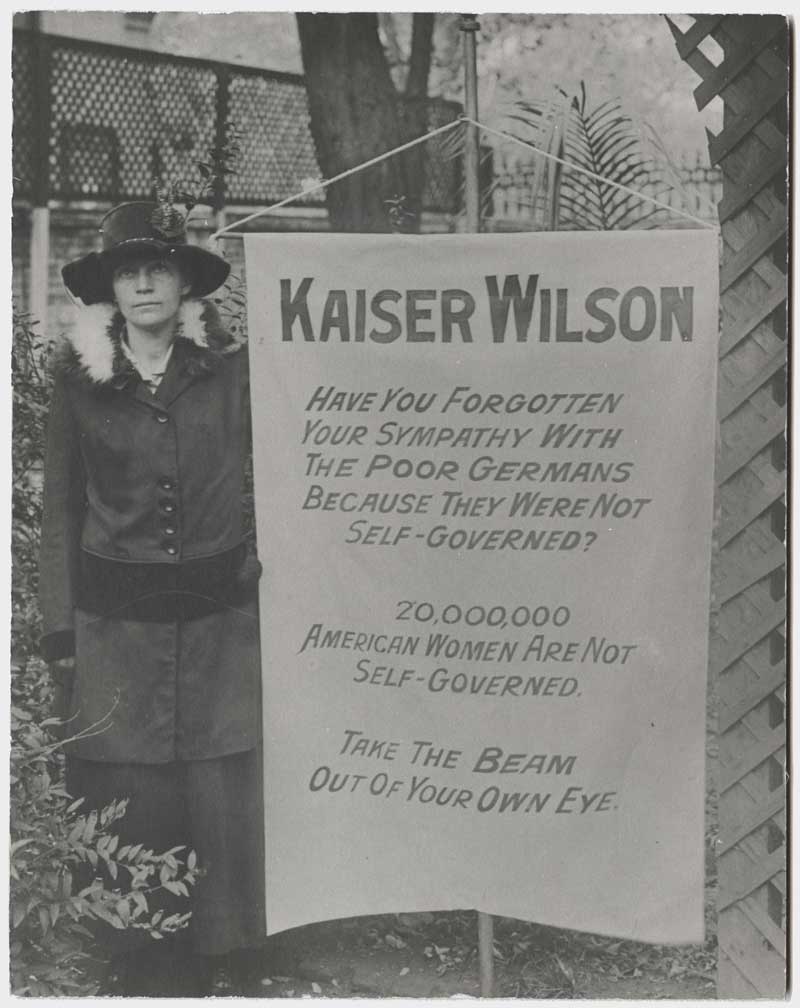

By the time the U.S. entered the Great War in 1917, 15 states had passed full women’s suffrage. In fact, Montana had already elected a woman, Jeanette Rankin, to the House of Representatives, highlighting the reality that women could run for national office but could not vote in national elections. As the war continued, Paul’s radical National Women’s Party protested peacefully outside the White House.

Suffragists maintained a silent picket with signs criticizing President Woodrow Wilson’s lack of support for women’s enfranchisement. At first tolerated by police, protesters endured harassment and attacks without police protection and were later arrested for obstructing traffic. In jail, Paul and others maintained their protest. After a hunger strike, they were force-fed and beaten brutally. Two months after their release, and almost exactly one year after Paul’s group began their protests, President Wilson announced his support for women’s suffrage on Jan. 9, 1918.

It took the election of 1918, which ushered in new members of Congress friendlier to suffrage, to pass the 19th Amendment, using the same language that Sen. Sargent had first introduced 40 years earlier in 1878. The House of Representatives voted to approve it May 21, 1919, and the Senate followed June 4. The legislatures of 36 states had to vote for it. By the end of 1919, 22 states had done so, but anti-suffragists defeated the measure in some Southern states, where white legislators opposed federal laws enforcing voting rights due to fears about disrupting segregation. Tennessee was the last state to ratify the amendment. As the story goes, a 24-year-old representative received a last-minute note from his mother urging him to vote yes. Eight days after the state of Tennessee voted to ratify the amendment, it was delivered via mail to the Secretary of State, becoming law on Aug. 26, 1920.

The 19th Amendment prohibits the denial or abridgment of the right to vote on the basis of sex, but it did not guarantee the right to vote to all women. First-generation Asian Americans of all sexes were barred from citizenship until 1952. Congress granted citizenship to Native Americans in 1924, but some states barred them from voting until 1957. Poll taxes, literacy tests and voter intimidation prevented generations of African American voters from going to the polls until the 24th Amendment banned poll taxes in 1964 and the Civil Rights Act of 1965 prohibited racial discrimination in voting. In Puerto Rico, local voting rights for all women were not assured until 1935, and language barriers still kept some from voting until bilingual ballots were required in 1975. To date, full access to federal voting rights are not assured in U.S. territories.