On April 22, 1915 at 5 p.m. a wave of asphyxiating gas released from cylinders embedded in the ground by German specialist troops smothered the Allied line on the northern end of the Ypres salient, causing panic and a struggle to survive a new form of weapon.

The attack forced two colonial French divisions north of Ypres from their positions, creating a 5-mile gap in the Allied line defending the city. This was the first effective use of poison gas on the Western Front and the debut of Germany’s newest weapon in its chemical arsenal, chlorine gas, which irritated the lung tissue causing a choking effect that could cause death.

A British officer described the effect of the gas on the French colonial soldiers:

“A panic-stricken rabble of Turcos and Zouaves with gray faces and protruding eyeballs, clutching their throats and choking as they ran, many of them dropping in their tracks and lying on the sodden earth with limbs convulsed and features distorted in death.”

There was no technology to protect the soldiers from this new weapon; an operational gas mask was not available, so the Allied soldiers improvised with linen masks soaked in water and “respirators” made from lint and tape.

Stunned by their overwhelming outcome of the attack, the Germans tentatively advanced, losing an opportunity to exploit their success.

After this initial use of poison gas, the technology and operational tactics of gas warfare quickly developed and were implemented by the Germans and the Allies throughout the war, including various gases and liquids, practical gas masks and gas alarm equipment. Combatant nations created chemical warfare units and schools to train them in the tactics of offensive and defensive gas warfare.

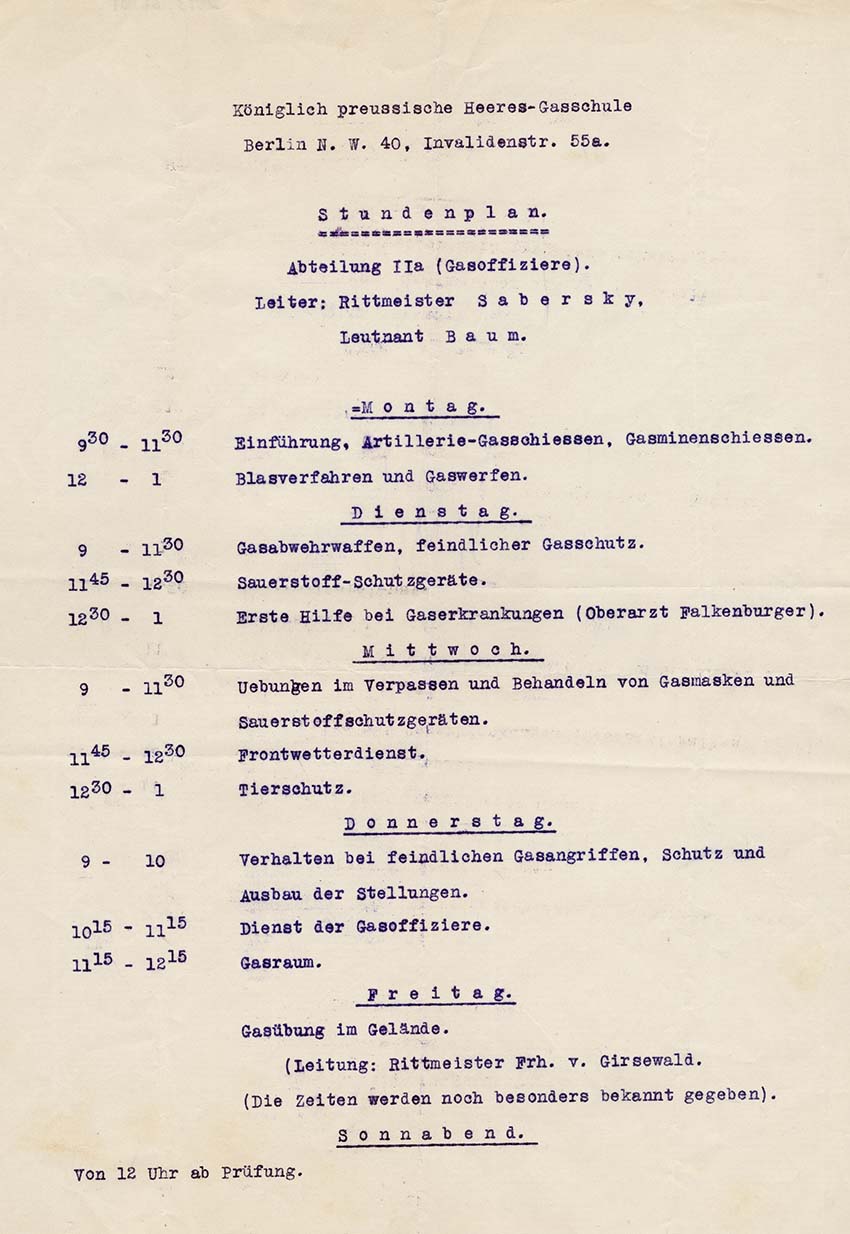

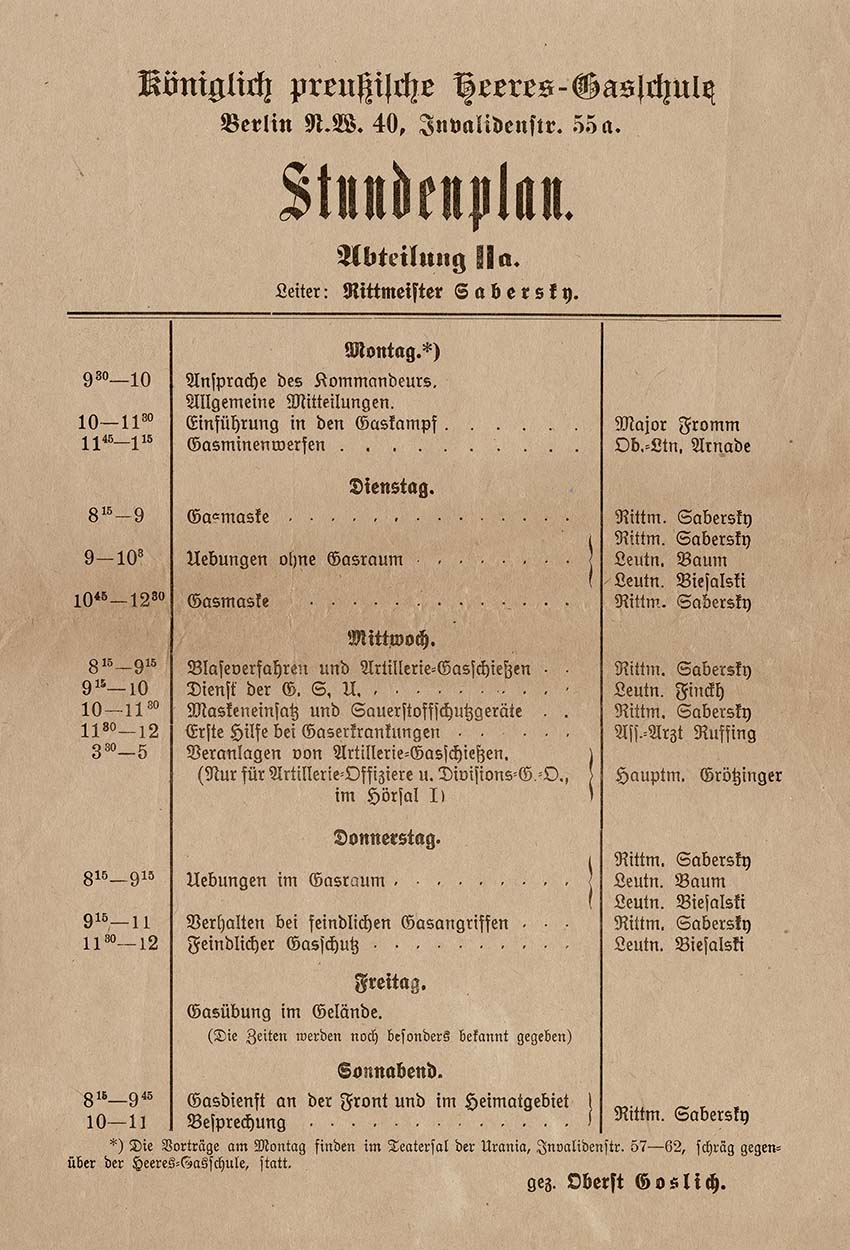

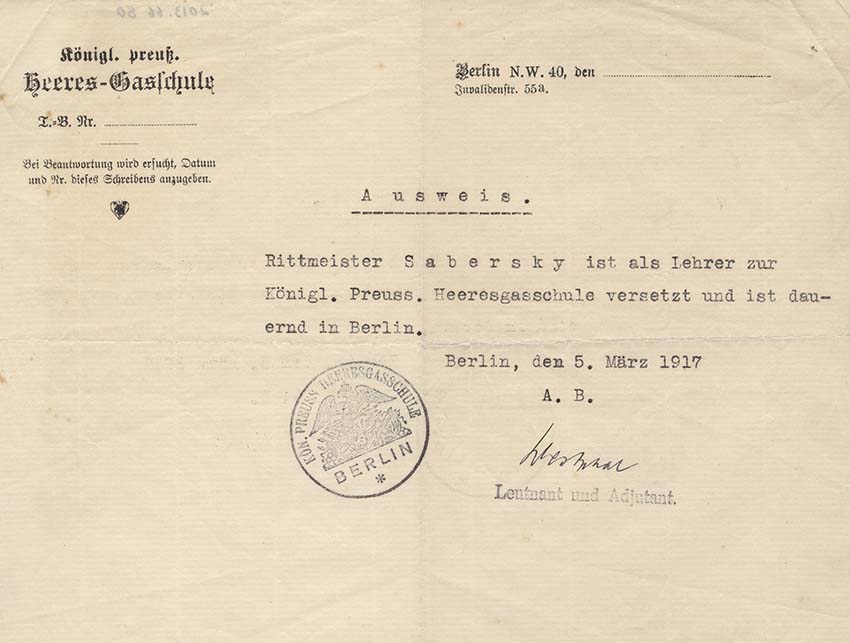

An archival collection (viewable through the Museum's online collections database) recently acquired by the Museum examines this new warfare from the experience of a German officer and gas school instructor. Kurt Eduard “Fritz” Sabersky was the commanding officer of Sanitary Company 3 of the Prussian Guard Reserve Corps from 1915-16 and then an instructor at the Royal Prussian Army Gas School in Berlin from March 1917 to the end of the war.

The collection includes:

- Sabersky’s identity card for his instructor position

- Draft of an instructional sheet “Gas Defense in the Trenches” listing instructions to prepare for an attack including “The sentry must also look out for suspicious odors” and “protect the telephone device.”

- Week long class schedules with subjects including:

- “artillery gas shooting”

- “mortar gas shooting”

- “gas defense weapons

- “first aid for gas illnesses"

- “exercises for handling of gas masks and oxygen-protection devices”

- “weather forecasting on the front” (the air pressure and wind direction were very important measurements to determine the effectiveness of a gas attack)

- “animal protection"

- “conduct during an enemy gas attack”

- “gas drill in the field”

In one weekly schedule there is a class on “Warfare agents” that discusses gas mixture formulations such as percentage of chlorine to percentage of phosgene and “Tactic for gas emission” discussing with measurements for the optimum length of gas cloud and amount of gas in tons.

By the end of the war the Germans produced the most poison gas with 68,000 tons, the French second with approximately 36,000 tons and the British produced approximately 25,000 tons. About three percent of gas casualties were fatal, but hundreds of thousands suffered temporary or permanent injuries.

More than 97 percent of the objects and documents from the Museum’s collection are donated. Learn how you can support the Museum with a donation.