“To write home frequently and regularly, to keep in constant touch with family and friends, is one of the soldier’s most important duties. Mothers and fathers will suffer if they do not hear often from sons fighting in France. In the present large companies, it is not possible for officers to write letters for their men, and every man must do it for himself.”

— General Orders, No. 66, from the General Headquarters, A.E.F., May 1, 1918

Mail service has historically been a cornerstone of American life and communication, and that was especially true for those serving overseas during World War I.

The first Army Post Office location established in France, APO No. 1, was in St. Nazaire on July 10, 1917. The last APO, opened on April 25, 1919, was No. 953. (Numbering of APOs was sequential but changed later to start with 700 so as not to be confused with the French and British postal services.) At the beginning, the Army Post Office was run by civilians, but General Orders No. 72 on May 9, 1918 started the Military Postal Express Service, whose post-war insignia was a silver running greyhound. It received and distributed all mail arriving in France for the A.E.F. and delivered the return mail it collected to civil postal authorities.

Mail and Courier Service Activities in the A.E.F., 1917-1919

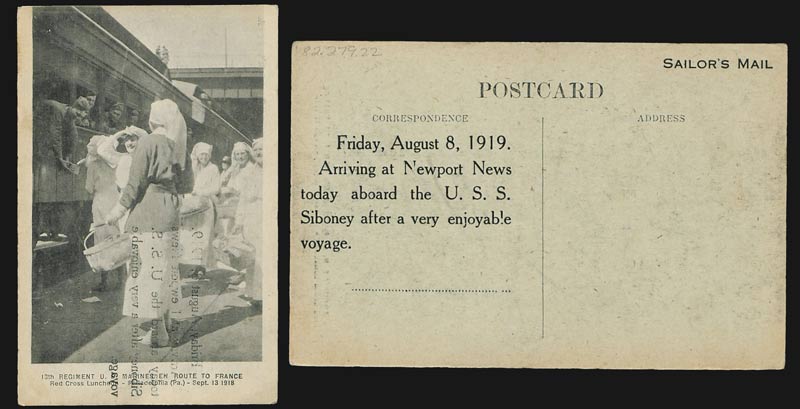

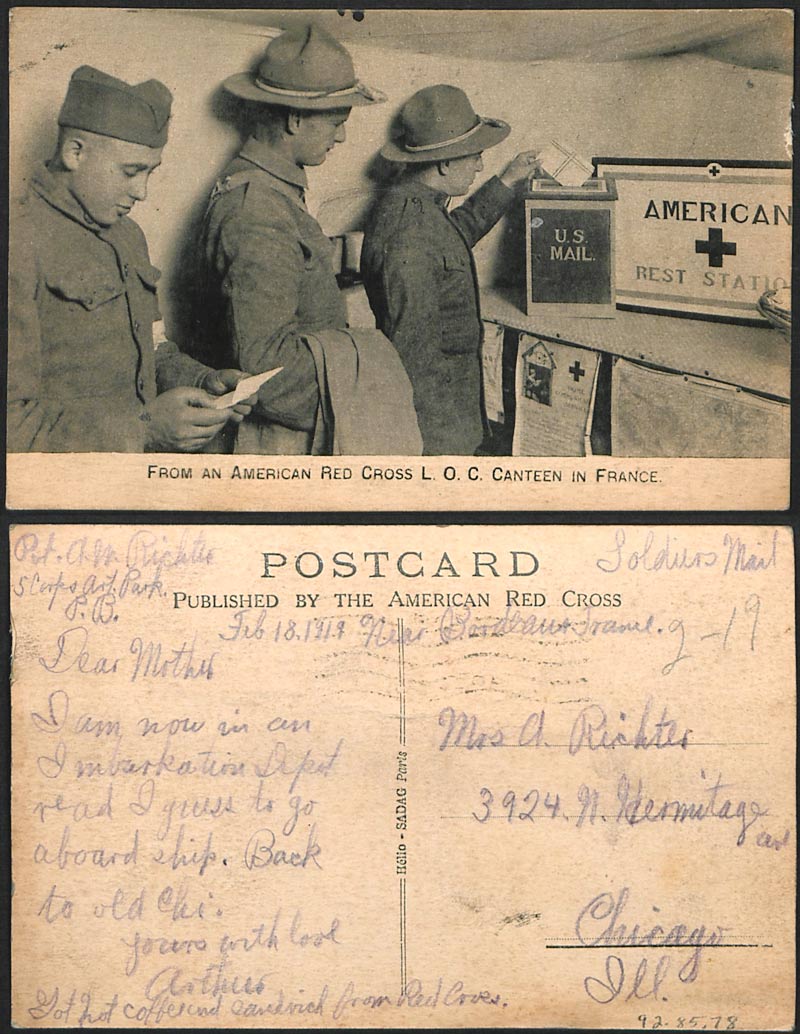

Service organizations in support of the U. S. military often provided stationary, postal cards and mailboxes at their stations for the convenience of the service personnel. By Oct. 3, 1917, General Orders No. 48 stated that “Soldiers, sailors and marines assigned to duty in foreign countries are entitled to mail letters free…by marking on the envelopes On Active Service (also OAS) or Soldier’s (Sailor’s, Marine’s) Mail.” Later additions to this included women military personnel, chaplains and officers. Regular U.S. postage was still required for mail sent inside the United States.

When new officers were inducted in the U.S. Army in 1917, they were presented with a small booklet, Management of the American Soldier. Included in its instructions was for officers to urge soldiers under their care to write home to relatives. Most needed no such encouragement. For the vast majority of service members and volunteers—soldiers, Marines, sailors, Coast Guardsmen, volunteer ambulance drivers, women telephone operators, nurses and Red Cross workers—the unique experiences of war and traveling abroad demanded to be shared. Reading the stories written across postcards, stationery and on the backs of photographs, families could be assured that their loved ones were alive and well.

To maintain a degree of confidentiality, service personnel were limited in the details that they could disclose in their letters back home. However, what they were able to reveal about their duties encouraged support for the war effort from the home front.

Post offices also transformed mailboxes into ballot boxes. Special election ballots for the 1918 election were printed and provided for service personnel overseas and in state-side camps so they could vote by mail. Return envelopes for ballots sent in the U.S. required 3-cent postage. One surviving example of a 1918 ballot is clearly printed “Soldiers’ Ballot Voted By Mail – Official Return Envelope for Absent Voter.” A cartoon from the A.E.F. newspaper Stars and Stripes also shows soldiers voting in 1918 by paper ballots with envelopes.

The more that post offices adapted to the needs of the era, the busier they became. A.E.F. Camp Crane in Allentown, Penn. reported its post office handling nearly 70,000 pieces of mail—including parcels—per week. Bridging military and civilian life, these post offices provided some of the most essential services during the war.

The Museum and Memorial was proud to host the unveiling ceremony for the United States Postal Service’s World War I: Turning the Tide Forever stamp for its first day of issue on July 27, 2018.

For more information about the history of the USPS, our educators recommend reading The United States Postal Service: An American History.