When the United States declared war on Germany in 1917, Native American individuals and nations faced a difficult decision. How might a people treated with inequity respond to a call of action for the safety of global democracy?

Despite the challenges, approximately 12,000 Native Americans served in roles across all aspects of the American Expeditionary Forces (A.E.F.) during World War I – non-segregated. One unique exception was the notable Code Talkers, a role in which some Native American soldiers served as a key communications defense.

What is Code Talking?

During any battle, transmitting information to troops quickly and securely is vital. In WWI, one of the fastest ways was to communicate through telephone lines. However, by 1917 these lines were often compromised by German spy technology. Germans tapped into the lines and used special technology like distance listening devices to stay ahead of Allied forces. Other communications methods such as buzzer phone codes were more secure but slow. Sending messengers was dangerous and unreliable, as on average one in four was captured or killed.

The unique nature of Native American languages, mainly unrecorded and unstudied inside and outside of the U.S., addressed this problem. Not understood by outsiders, including Germans, Native American Code Talkers could send messages that the enemy could not decipher, successfully concealing battle plans and tactics which led to several Allied victories.

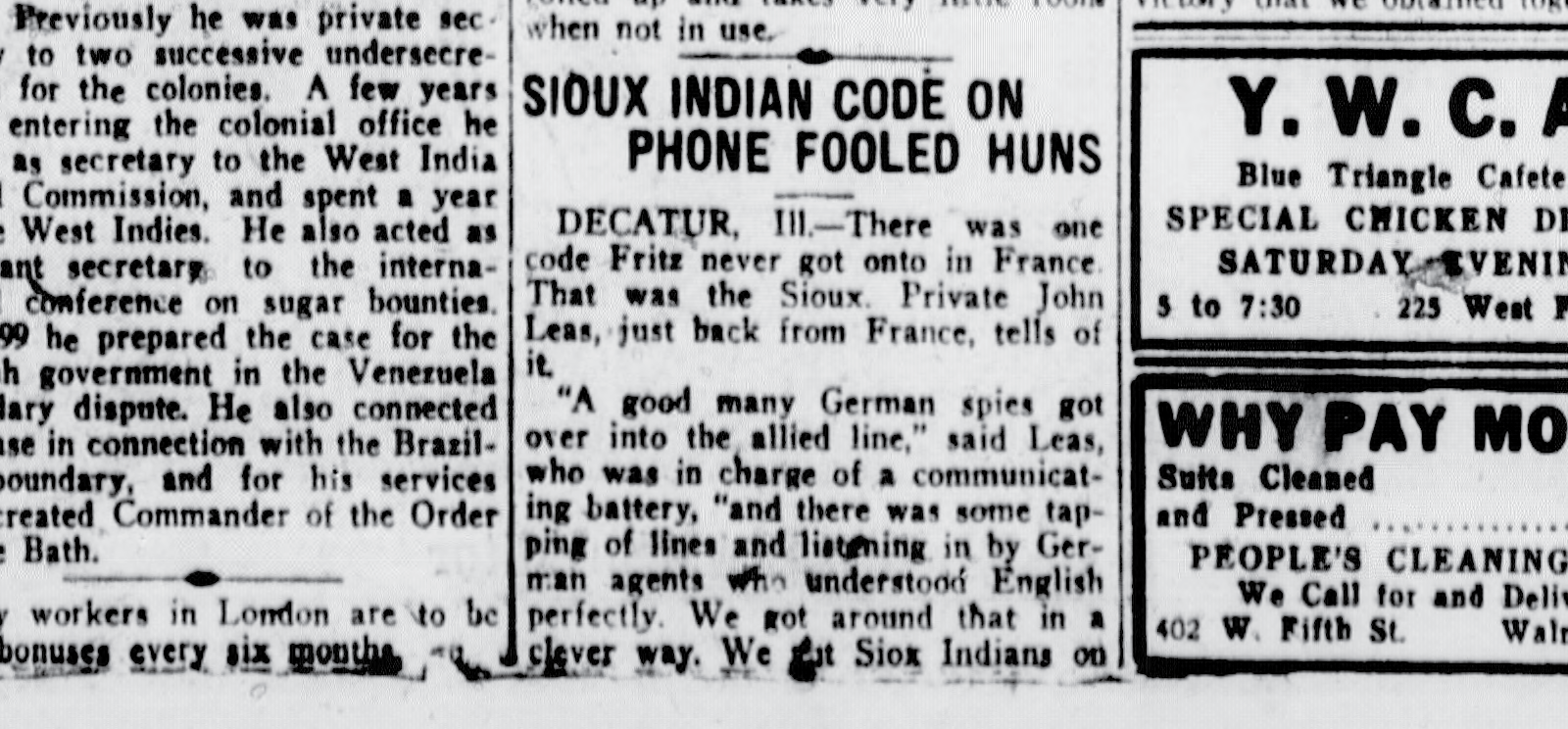

DECATUR, Ill.—There was one code Fritz never got onto in France. That was the Sioux. Private John Leas, just back from France, tells of it.

"A good many German spies got over into the allied line," said Leas, who was in charge of a communicating battery, "and there was some tapping of lines and listening in by German agents who understood English perfectly. We got around that in a clever way. We got Siox [sic] Indians on the telephones to send and receive orders."

The Oklahoma City Times. (Oklahoma City, OK) 28 Jun. 1919, p. 5. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/sn86064187/1919-06-28/ed-1/.

Who were the Code Talkers?

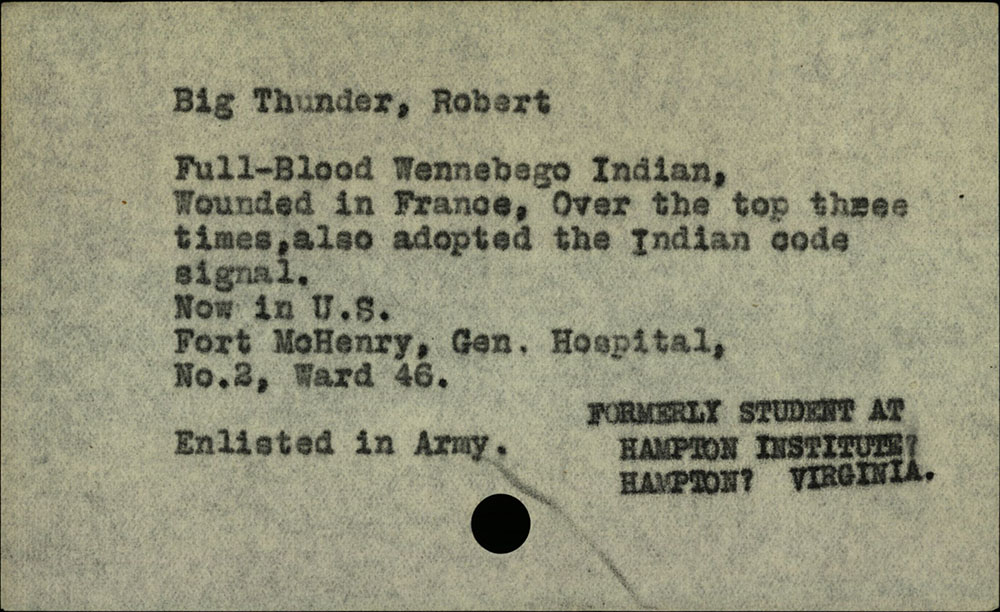

The first recorded use of Native American Code Talkers took place shortly before June 21, 1918. During a battle against German forces in France near Château Thierry, two men from the Ho-Chunk Nation – Robert Big Thunder and John Longtail – were relied upon to send necessary communications that the enemy could not understand.

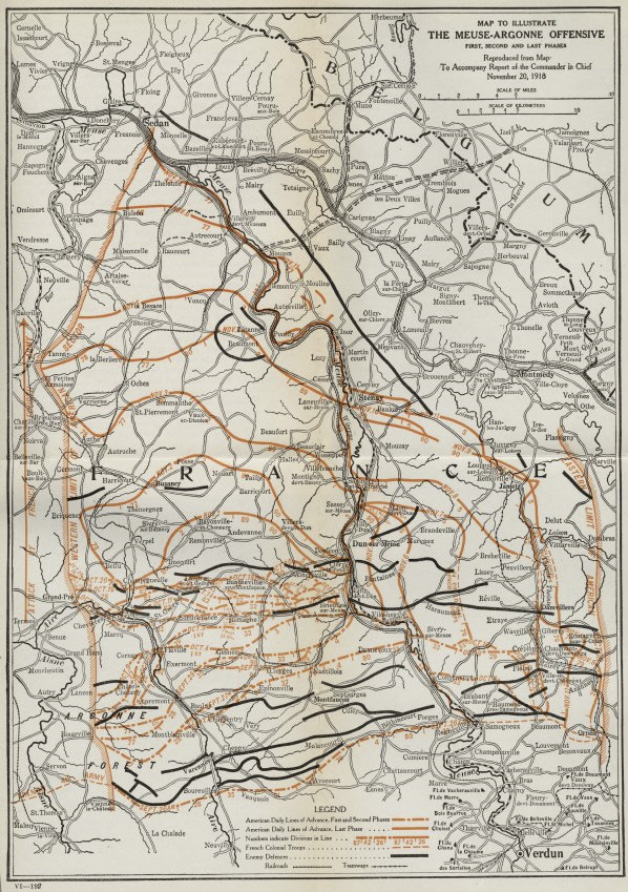

Another clear record occurred during the Meuse-Argonne Campaign in France on Oct. 7-8, 1918. The Eastern Band Cherokee operated as Code Talkers after a test proved that all Allied communications were being intercepted by German forces. Soon after, men from the Choctaw and Oklahoma Cherokee Nations were employed as Code Talkers as well. A group of eight Choctaw Code Talkers enabled Americans to capture an entire German line with minimal losses.

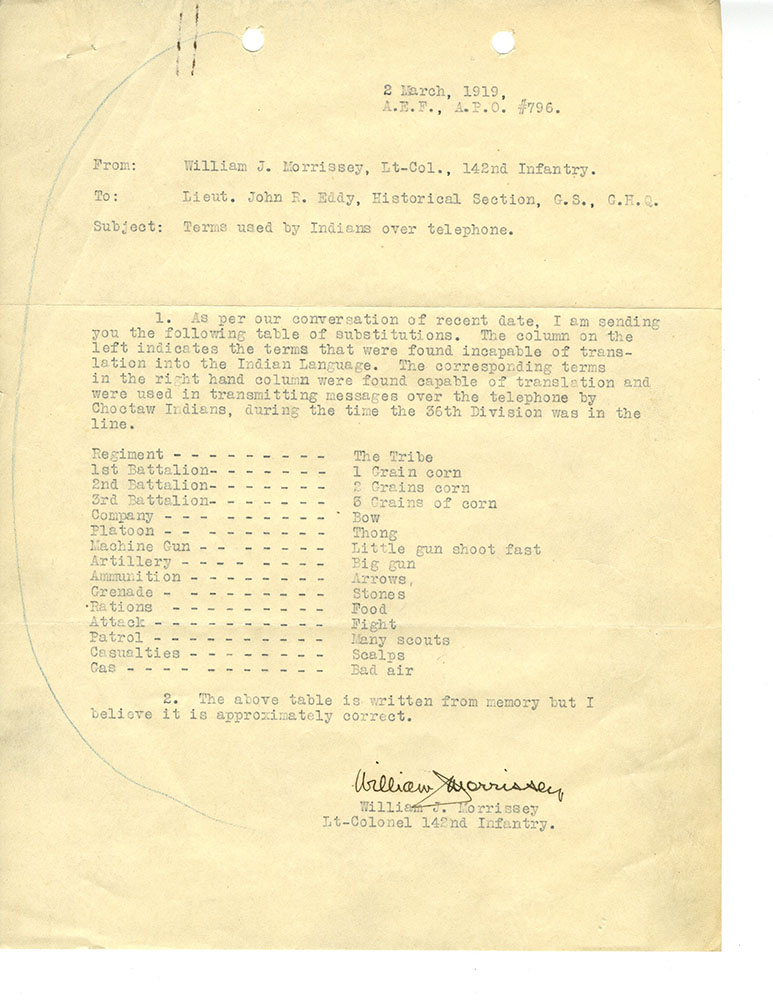

From Nov. 5-10, 1918, 18 enlisted men and three non-commissioned officers – all Native American – were tasked with creating code words for essential communication that did not have equivalents in Choctaw. They completed their task just as the armistice was called, so their new codes were not used during WWI.

This letter was sent to Lieutenant John Eddy as part of a data collecting initiative about Native Americans in Service. Eddy was the former Superintendent of the Crow Reservation in Montana and decided to send surveys out while in recovery from being gassed on the battlefield. The letter shows the Choctaw codes designed by the selected group of Native Americans who had been tasked with their creation right at the end of the war.

Individuals from some other nations such as the Comanche have left some information behind on documents. For example, Calvin Atchavit of the 90th Division's “Indian Card” lists him as having earned a War Cross from the Belgian government for “talking over the lines when they were tapped by the enemy.” The details of so many have yet to be uncovered, as the military bureaucracy formally recorded so little.

Despite the U.S. government’s attempts to strip Native Americans of their languages in boarding schools, these individuals took on the duties asked of them without the expectation of recognition.

Legacy and Delayed Recognition

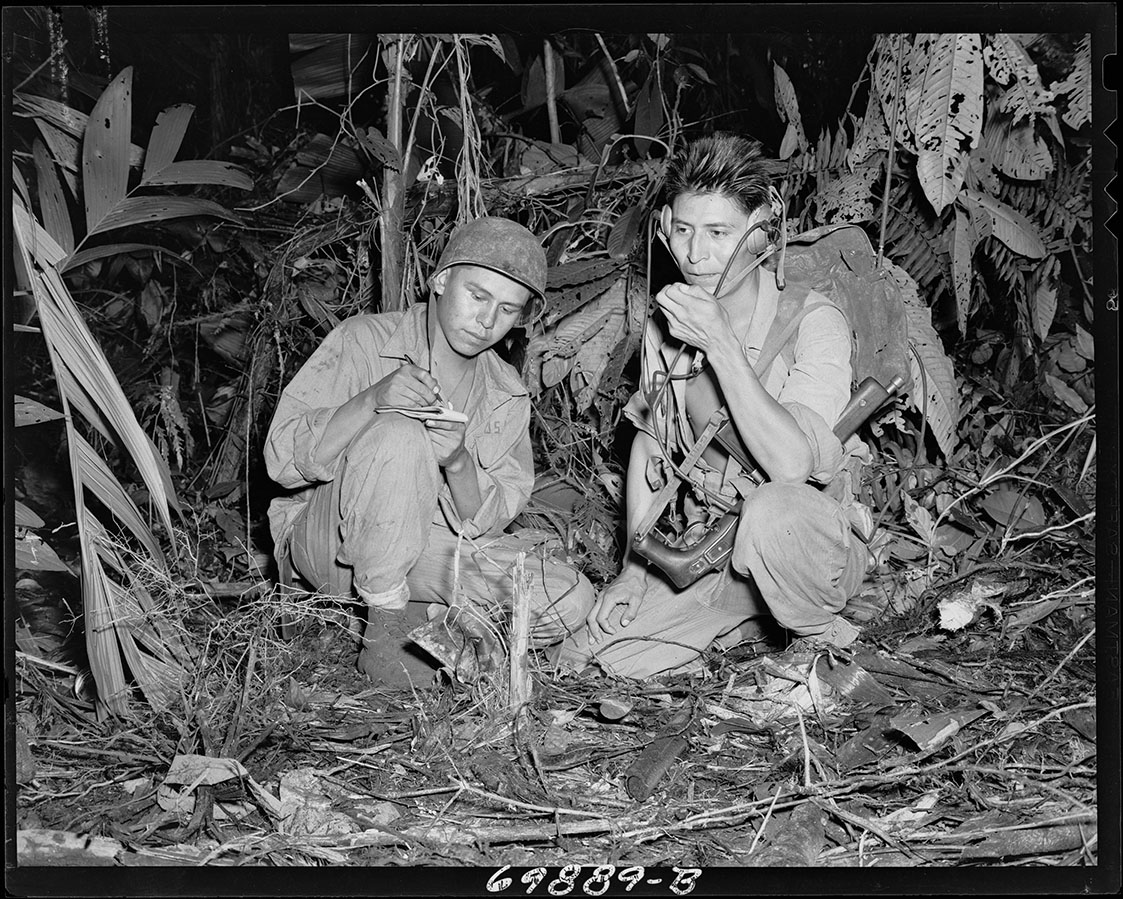

World War I Code Talkers played a crucial role in the U.S. military that others could not, thanks to their languages. After decades of the U.S. government trying to erase Indigenous languages, these soldier’s multilingualism turned out to be an asset to the Allied cause and to the U.S. military. Those who shared stories with their families about their work and their service – steeped uniquely in their cultural identity – left their communities with great pride. Additionally, the U.S. military did not forget about these communication roles during WWI. Their key success guided the use of Code Talkers for vital communications during the next global war: World War II.

Despite the WWI Code Talkers’ contributions, the U.S. government did not immediately recognize them for their special actions. Much of what is known today comes from the statements of individuals, their commanding officers and their families. Their own communities began efforts to gain recognition for WWI Code Talkers in 1986, when the Choctaw Nation established their own medal and memorial. Since then, many other Native American communities have undertaken memorialization efforts. In 2008, the Code Talkers Recognition Act was passed, leading to a 2013 Congressional Gold Medal Ceremony for both WWI and WWII Code Talkers, with each nation creating its own medal design.

Virtual Reality Experience

The Code Talker story like you've never seen it before:

Our Worlds tells the incredible story of America’s original Code Talkers in stunning virtual reality – immersing viewers in the presence of Choctaw soldiers fighting in France, presented in XR360°.

Located in the Main Gallery during open hours.

Learn more about Code Talkers:

Want to know more about individual Code Talkers and their stories? Watch Dr. Bill Meadows, historian and author of “The First Code Talkers: Native American Communicators in World War I,” as he explores recent discoveries in research and delves into the post-war impact and popular myths of the first Code Talkers.

For Classrooms:

Explore the “How WWI Changed America” teacher toolkit, which includes a dedicated section on Native American Service. Find resources such as a short documentary video, primary sources, a podcast and tools for analysis, as well as a lesson to help students learn about Native American service and citizenship.

Other videos to watch:

The contributions of Native Americans to the war effort helped win the war and, in 1924, citizenship for all Indigenous peoples in the U.S. This short video shares a small portion of their story.

After the stripping of their weapons and confinement to reservations in the late 19th century, many Native American nations -- especially Plains communities with strong warrior societies like Kiowa and Comanche -- recognized the United States' entrance into the World War I as a time when they could “become warriors again.” As Native communities sent their young men to serve, they revived and openly practiced sacred spiritual traditions in direct defiance of United States reservation and assimilation policies.

When they returned from overseas, veterans did not shed their warrior roles but embraced their communities’ concepts of warriors as leaders and those entrusted to ensure their people’s survival. In doing so, many veterans became spiritual advocates, becoming active participants in the reemergence of traditional expressions of faith as well as advocates for newer spiritual practices, like the Native American Church.

Specialist Curator for Faith and Religion Patricia Cecil investigates their experiences.

From combat and cryptology to logistics and labor, approximately 12,000 American Indian soldiers served with the American Expeditionary Forces during the Great War. Despite their service and the accolades awarded for their actions, many were not officially recognized as citizens by the United States government.

In supporting the war effort – a means of honoring and protecting the land they had inhabited for millennia – they hoped to gain this status under the law.

On the 100th anniversary of the Indian Citizenship Act, join specialist curator Natalie Lovgren as she delves into the history and legacy of American Indian service during WWI.